– By Pranav Menon

– Research Scholar, Centre For Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Introduction

In his work, Regional Trade Agreements and the Poverty Agenda, Lim seeks to analyse the intersectionalities with the General System of Preferences (GSP) scheme under Article XIX GATT and the rapid proliferation of Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs), which may be seen as an alternative to the GSP scheme, possibly eroding the idea of ‘Enabling Clause’ for developing countries.

Through the course of this review, I would like summarize the author’s opinion by tracing the roots of the General System of Preferences scheme and its relevance for developing countries to gain equitable market access and seek harmonisation of trade benefits through Special & Differential Treatment (S&D) provisions within the WTO agreements. This review is an attempt to appreciate the author’s idea regarding the phenomena of rising RTAs between WTO members and their role in dismantling or progressively harmonising the uniform trade regime envisaged by WTO. Further, the author intends to trace the design of S&D provisions within these RTAs and indicate how preferential access to poorer nations have been diluted with time through these regional mechanisms. The conceptual and practical difficulties within the S&D framework into workable principles of RTA design thus as per the author undermines the notion of global justice within international trade which such preferential arrangements for poor nations sought to achieve.

Summarizing the Article

The Enabling Clause mechanism, as Lim explains was the product of a GATT decision vehemently sought by developing countries to allow them better terms of trade with preferential market access in developed countries without fulfilling the mandate of reciprocity, in an otherwise unequal trade regime. While the clause sought S&D provisions for greater flexibility and exceptions to existing legal obligations under the GATT and became the existing basis for a Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) for developing countries, the system became non-obligatory as the US and European Community could not agree on a ‘global’ generalized system. Lim highlights these GSP programmes fail to accommodate concerns of global redistributive justice owing to the ineffective language of Part IV of GATT, leaving poor states to fend and renegotiate their commitments themselves, while the requirements of the BOP exception continue to remain difficult to fulfil. He analyses the India- GSP case, to indicate how the Appellate Body has sought to interpret the GSP mechanism is not a generalized system and differential treatment between developing countries is nonetheless allowed where such treatment is at least ‘rationally related’ to the different economic, financial and developmental needs of the developing country beneficiaries.

While the norm of Most Favored Nation and other non-discriminatory principles are exempted within RTAs and preferential market access under GSPs, the motivations to enter into an RTA along with political and economic considerations, is seemingly to achieve trade liberalization which cannot be otherwise achieved or not sought multilaterally. Lim understanding of RTAs, as per the stringent requirements of Article XXIV of the GATT, must co-equally liberalize ‘substantially all trade’ between partners based on reciprocity. The notion of justice is defined in terms of equality of concessions, unlike in developing country preferences which accord favorable treatment at the expense of other third country trading partners. The less than full reciprocity envisaged under the GSP applies not merely preferential treatment to specific countries but also only to specific goods. Furthermore, the grounds for providing GSP programmes is around the principle of providing market access as a means of promoting growth and development within developing countries, while the typical reason to formulate an RTA is based on purely economic grounds.

While, the approach of US and EC GSP programmes have sought to harmonise it with newly emerging FTAs and EPAs, Lim believes that FTAs can and should address poverty issues by incorporating S&D provisions to complement an investor friendly, export oriented policy of growth and development. Such RTAs can be touted as a ‘developmental tool’ if accompanied with range of poverty reduction tools such as aid for trade, financial and technical assistance and capacity building, rule of law by plugging the low capital deficiency within poor developing nations. Through RTAs, the ‘Investment gap’ could be filled by private FDI instead in these developing nations rather than relying on foreign aid, thus fostering a growth driven by exports earnings and growth equals development. While quintessential US style liberalized FTAs do emphasize on trade and investment as most important development tools, it will risk the charge of ideology no different from the various conditionalities imposed by international finance institutions such as the IMF. Technical assistance and capacity building provisions within these arrangements could remind us of those approaches to development which emphasize on the holistic role of aid, technology transfer, education as well as rule of law.

However, Lim continues to believe that the strict reciprocal nature of RTAs seem to push them in a direction in contravention to the redistributionist agenda propagated under the developing countries preferences scheme, as he believes that any regime based on trade liberalization – multilateral, regional or bilateral – would tend to erode preferential market access to developing countries. The Doha Development Agenda (DDA) is crucial in this regard to foster developing countries participation in the redistributionist rule making within the multilateral trade regime. Thus, Lim feels obligated to warn against RTAs as a threat to the WTO mechanism which has long presented itself as a principal negotiating forum between the developed and developing countries, especially undermining the gains in the S&D provisions.

The Doha Ministerial Declaration of 2001 provided for a specific commitment to address the needs and interests of developing nations. Paragraph 44 of the Declaration stipulates the mandate to review and strengthen S&D provisions to make them more precise, effective and operational as per the needs of the developing nations, which highlighted the clear mandate to address the issue of poverty. Another clear indication of this mandate is visible in the 2004 July Framework which sought to provide basis for guiding negotiations forward in areas of agriculture, non-agricultural market access, services and trade facilitation. While the elimination of agricultural subsidies by 2013 and Duty Free Quota Free (DFQF) agri-market access were notable outcomes, little progress on reducing trade distorting domestic support for farmers and agricultural tariffs among developed states highlights the apathy towards fulfilling the Doha agenda. The principal cause for the 2008 collapse is associated to the idea of a Special Safeguard Mechanism (SSM) a permissive protection which is accorded to developing countries with a price trigger mechanism to protect their domestic products from import surges.

Lim opines that the stalling of multilateral trade talks over distributive justice concerns within the WTO could be juxtaposed with an inverse relation in the proliferation of present day RTAs. The more staunchly developing states maintain their stance on the Doha agenda, greater will be the incentive for developed states to pursue competitive liberalism through the rapid conclusion of RTAs. Lim is overtly critical of the partner selection in the RTAs as they often bypass poorest countries which have minimal resources. Furthermore, RTAs have been accused of trade diversion and promoting unwarranted bilateralism, as many economists believe that their conclusion among nations leads to exclusion of certain markets and disadvantage as against competitor nations. Rather than extending membership to such RTAs in a bid to make them more multilateral, they would be more representative and accessible if they took into account concerns of poorer nations.

Despite being critical of how RTAs are presently operationalized, Lim strongly vouches for the ASEAN treaty practice as the closest actual example of a genuine intent to build S&D treatment through Differentiation, Graduation and robust mechanism to identify members to benefit of these provisions. At the multilateral fora, there is a need for use of multiple criteria as opposed to a single criterion for differentiation i.e. per capita income approach or define S&D treatment by circumstance and events (Disasters, public emergencies) fulfilling the need to locate countries on an apriori basis on a previously contested criteria. The lack of any existing multilateral arrangement to codify the principles and objectives of S&D treatment owing to its perception among developing states itself to be an organic formulation, compounds the difficulty of inculcating this standard into the RTAs framework. Subsequent to the Uruguay Round, scholars have identified 5 possible variants, in depth and seriousness, of the S&D treatment obligation namely: increased trade opportunities to poor nations by virtue of the good faith clause under Article XXXVII of GATT, safeguarding specific interests under Article 9.1 of Safeguards Agreement, lesser obligations under Agreement on Agriculture, technical assistance to maintain sanitary and hygiene standards under Article 9 SPS Agreement and longer timeframes to meet harmonise trade interests with global regime. This lack of bindingness and precision within these obligations coupled with the inoperative nature of these provisions is what Paragraph 44 of the DDA seeks to encapsulate.

On the question of whether these RTAs can weave in global justice concerns, Lim argues that as RTAs are couched in the language of formal equality creates a lawful discrimination and selective concessions against third parties as well as does not often create equal outcomes for participating partners. The GSP system on the other spectrum intends to take a cosmopolitan view of global justice based on substantive conception of equality beyond the formalistic sovereign idea to facilitate just outcomes, equity and opportunities by according special mechanisms to developing countries. The present day RTAs are motivated by a slowdown of global trade talks due to conflicts in conceptions of distributive justice sought by developing countries, with such arrangements according larger powerful countries greater bargaining strength in the context of actual trade negotiations. Lim though concludes on an optimistic note hoping that these arrangements borrow redistributive justice tools to stabilize trade between unequal partners to address the poverty agenda.

Conclusion

The approach adopted by Lim in analysing Regional Trade Agreements in the prism of distributive justice ideals reflects his leaning as a TWAIL scholar. The WTO trading system has conveniently tried to sidestep the concept of ‘development’, which forms the basis for global justice, for pursuing a harmonised trade regime. The language of the S&D provisions throughout the WTO agreements merely provide lip service to the ideas of substantive equality rather than creating any formal binding mechanism to implement these provisions for the benefit of poor nations. The inability of DDA to move forward with its contentious issues has resulted in the splintering of the multilateral trade mandate and countries view RTAs as an effective means to facilitate deeper economic integration and trade benefits. Simon Lester believes RTAs through faster negotiations and tailor made trade specific concerns enable parties to liberalize beyond levels achievable under multilateral consensus and invigorating new opportunities of regional integration, improved trading capacity and institution building. While trade creation through such arrangements can foster regional development and boost sub national trade, there is a growing scepticism of these mechanisms being used as a trade diversionary tactic by fostering lawful discrimination against other developing states.

However, RTAs today are more often being negotiated by developing and LDCs for the fear of being left behind or severely disadvantaged under the existing trade regime. While certain RTA mechanisms like ASEAN FTAs do provide for incorporation of S&D provisions, most of these arrangements premised on the idea of reciprocity are highly incentive based for the parties and does not weave in the narrative of differential treatment for unequal trading partners. Their conclusion is highly political with inherent power structures as bargaining chip for natural trading parties is not as skewed in comparison to countries which do not carry out substantial trade amongst each other. The underdeveloped countries with minimal resources and low trading patterns may feel excluded as these RTAs can conveniently avoid them. The poverty and development agenda must be revived multilaterally rather than create these fragmented frameworks through RTAs for according trade concessions to favourable partners. The multiplicity of RTAs through complex Rules of Origin mechanism, differing standards and overlapping jurisdictions, decreases the net welfare gains made from trade benefits. Jagdish Bhagwati characterises these complexities and dissimilarities within the RTAs as a ‘Spaghetti Bowl’ while arguing against their rapid proliferation as they tend to deviate from principles of redistribution of trade benefits.

As an independent researcher, I believe the RTA mechanism is here to stay but it does encompass scope for democratization within trading partners by considering region and context specific trade concerns, which may foster development especially in the Third World. However, it is crucial that these arrangements do not derail the substantive justice demands of the developing nations within the multilateral trading regime, as envisaged in the DDA. An inclusive RTA mechanism taking into account S&D treatment obligations can facilitate efficient and redistributive trading patterns among developed and developing states alike.

References

- Chen Leng Lim, “Regional Trade Agreements and the Poverty Agenda” in J. LINARELLI (ED.), RESEARCH HANDBOOK ON GLOBAL JUSTICE AND INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC LAW (Elgar, 2013), 96-120.

- Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) used to refer to the genus, of which Customs Union, Free Trade Agreements, Economic Partnership Agreements, Preferential Trade Agreements are but species. These words are used interchangeably by the Researcher through the course of the paper.

- Since the establishment of WTO, the number of RTAs has grown rapidly. During GATT years only 124 RTAs were entered into while in the succeeding 10 years of WTO saw an additional 196 notified RTAs. Currently, 228 RTAs notified to WTO and approximately 50 additional RTAs are being negotiated. See, James Crawford and RV Florentino ‘The Changing Landscape of Regional Trade Agreements’, WTO working paper (Geneva, WTO, 2005).

- GATT B.I.S.D. (26th Supp) 203–04 (1980).

- Unlike the European System, the US offered GSP grants preferences to listed beneficiary countries in respect of specific listed prices, applies the concept of gradation and that of competitive need limitations. The former serves to remove poor nations which have made progress from GSP, while latter caps the concessions made to specific beneficiaries for specific products every year. This model has been criticized for inducing developing nations into preconditions which may not be trade specific.

- First, critics have pointed out that Part IV is not “obligatory” but “declaratory” in nature. Secondly, “non-reciprocity” has become a negotiation issue in practice. In short, developed countries are not legally obligated, indeed they cannot in practice be simply subjected to a legal obligation, to negotiate successfully with developing countries on the basis of less than full reciprocity. Lee, Yong-Shik (2008) “Development and the World Trade Organization: Proposal for the Agreement on Development Facilitation and the Council for Trade and Development in the WTO” in Yong-Shik Lee (ed.) Economic Development through World Trade: A Developing World Perspective (Hague: Kluwer) pp. 8-10.

- European Communities – Conditions for the Granting of Preferences to Developing Countries, WT/DS246/AB/R, (4 April 2004).

- US FTAs with Latin American former GSP beneficiaries, a search for so called NAFTA parity is evident, while many argue it is favourable long term choice than the US GSP system which is more onerous than increased access to a rich country’s market under the FTA.

- Prompted by the external pressure through the adverse ruling in the EC Bananas III ruling, the EU accords its developing partners with a choice between having a ‘modified’ GSP preference scheme or entering into an EPA with EU which grants longer time frame towards liberalization beyond the 10 year requirement within GATT-WTO mechanism. See, Bormann, Axel, Gromann, Harald and Koopman, Georg (2006) “The WTO Compatibility of the Economic Partnership Agreements between the EU and the ACP Countries”Intereconomics (March/April): 115–20. Similarly, China and ASEAN’s treaties contain S&D provisions to the extent that Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam are allowed longer phase-in periods for trade liberalisation. See, Chin, David (2010) “ASEAN’s Journey Towards Free Trade” in Chin Leng Lim and Margaret Liang (eds.) Economic Diplomacy: Essays and Reflections by Singapore’s Negotiators (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies/World Scientific): 209–44.

- WT/MIN(01)/DEC/1, 20 November 2011.

- Ismail, Faizel (2009) “An Assessment of the WTO Doha Round July-December 2008 Collapse” World Trade Review 8: 579–605.

- This creates a scenario of Domino Effect, where the more nations that join FTAs, the greater the need for non-members to negotiate FTAs just to keep their goods on competitive terms. The Domino Effect is strongest when a trading partner has negotiated multiple FTAs.

- Income, Degree of vulnerability of trading partner, special criteria for land-locked nations and small island states.

- Lim, Chin Leng (2011) “The Conventional Morality of Trade” in Chios Carmody, Frank J. Garcia and John Linarelli (eds.) Global Justice and International Economic Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): 129–52.

- Kessie, Edwini (2007) “The Legal Status of Special and Differential Treatment Provisions in the WTO Agreements” in George A. Bermann and Petros C. Mavroidis (eds.) WTO Law and Developing Countries (Cambridge University Press)

- Simon Lester et. al., World Trade Law – Texts, Materials and Commentary, (Oxford, 2012) pp.332-34.

- J Bhagwati, The Wind of Hundred Days: How Washington Mismanaged Globalization (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 2000)

onducted a total of five underground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Pakistan followed, claiming 5 tests on May 28, 1998, and an additional test on May 30. The unannounced tests created a global storm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in South Asia. On May 13, 1998, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctions on India, mandated by Section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and applied the same sanctions to Pakistan on May 30. Some effects of the sanctions on India included: termination of $21 million in FY1998 economic development assistance; postponement of $1.7 billion in lending by the International Financial Institutions (IFI), as supported by the Group of Eight (G-8) leading industrial nations; prohibition on loans or credit from U.S. banks to the government of India; and termination of Foreign Military Sales under the Arms Export Control Act. Humanitarian assistance, food, or other agricultural commodities are excepted from sanctions under the law.

onducted a total of five underground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Pakistan followed, claiming 5 tests on May 28, 1998, and an additional test on May 30. The unannounced tests created a global storm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in South Asia. On May 13, 1998, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctions on India, mandated by Section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and applied the same sanctions to Pakistan on May 30. Some effects of the sanctions on India included: termination of $21 million in FY1998 economic development assistance; postponement of $1.7 billion in lending by the International Financial Institutions (IFI), as supported by the Group of Eight (G-8) leading industrial nations; prohibition on loans or credit from U.S. banks to the government of India; and termination of Foreign Military Sales under the Arms Export Control Act. Humanitarian assistance, food, or other agricultural commodities are excepted from sanctions under the law.

The first ministerial level meeting of QUAD was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Before this, the QUAD had

The first ministerial level meeting of QUAD was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Before this, the QUAD had AusIndEx is an exercise between India and Australia which was first held in 2015.The Australian

AusIndEx is an exercise between India and Australia which was first held in 2015.The Australian

On recommendations of the Japanese government, the four countries met at Manila, Philippines for ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) originally, but also ended up having a meeting of what we call the first meeting of four nation states on issues of

On recommendations of the Japanese government, the four countries met at Manila, Philippines for ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) originally, but also ended up having a meeting of what we call the first meeting of four nation states on issues of  On his official visit to India, Japanese PM Mr. Shinzo Abe reinforced the ties of two nations, i.e., Japan and India with his famous speech about

On his official visit to India, Japanese PM Mr. Shinzo Abe reinforced the ties of two nations, i.e., Japan and India with his famous speech about  In 2007, Japanese President Shinzo Abe resigned from his post citing health reasons. This had a significant impact on QUAD as he was the architect & advocate of QUAD. His successor, Yasuo Fukuda, did not take up QUAD with such zeal leading to dormancy of the forum. (

In 2007, Japanese President Shinzo Abe resigned from his post citing health reasons. This had a significant impact on QUAD as he was the architect & advocate of QUAD. His successor, Yasuo Fukuda, did not take up QUAD with such zeal leading to dormancy of the forum. ( Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, also called Great Sendai Earthquake or Great Tōhoku Earthquake, was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake which struck below the floor of the Western Pacific at 2:49 PM. The powerful earthquake affected the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island, and also initiated a series of large tsunami waves that devastated coastal areas of Japan, which also led to a major nuclear accident. Japan received aid from India, US, Australia as well as other countries. US Navy aircraft carrier was dispatched to the area and Australia sent search-and-rescue teams.

Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, also called Great Sendai Earthquake or Great Tōhoku Earthquake, was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake which struck below the floor of the Western Pacific at 2:49 PM. The powerful earthquake affected the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island, and also initiated a series of large tsunami waves that devastated coastal areas of Japan, which also led to a major nuclear accident. Japan received aid from India, US, Australia as well as other countries. US Navy aircraft carrier was dispatched to the area and Australia sent search-and-rescue teams.  India and Australia signed the

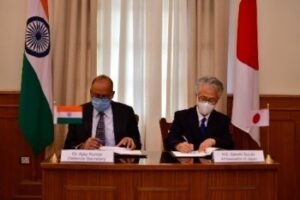

India and Australia signed the  The India-Japan Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy was signed on 11 November, 2016 and came into force on 20 July, 2017 which was representative of strengthening ties between India and Japan. Diplomatic notes were exchanged between Dr. S. Jaishankar and H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India. (

The India-Japan Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy was signed on 11 November, 2016 and came into force on 20 July, 2017 which was representative of strengthening ties between India and Japan. Diplomatic notes were exchanged between Dr. S. Jaishankar and H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India. ( The foreign ministry

The foreign ministry The Officials of QUAD member countries met in Singapore on November 15, 2018 for consultation on regional & global issues of common interest. The main discussion revolved around connectivity, sustainable development, counter-terrorism, maritime and cyber security, with the view to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the

The Officials of QUAD member countries met in Singapore on November 15, 2018 for consultation on regional & global issues of common interest. The main discussion revolved around connectivity, sustainable development, counter-terrorism, maritime and cyber security, with the view to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the  The 23rd edition of trilateral Malabar maritime exercise between India, US and Japan took place on 26 September- 04 October, 2019 off the coast of Japan.

The 23rd edition of trilateral Malabar maritime exercise between India, US and Japan took place on 26 September- 04 October, 2019 off the coast of Japan.  After the first ministerial level meeting of QUAD in September, 2019, the senior officials of US, Japan, India and Australia again met for consultations in Bangkok on the margins of the East Asia Summit. Statements were issued separately by the four countries. Indian Ministry of External Affairs said “In statements issued separately by the four countries, MEA said, “proceeding from the strategic guidance of their Ministers, who met in New York City on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly recently, the officials exchanged views on ongoing and additional practical cooperation in the areas of connectivity and infrastructure development, and security matters, including counterterrorism, cyber and maritime security, with a view to promoting peace, security, stability, prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.”

After the first ministerial level meeting of QUAD in September, 2019, the senior officials of US, Japan, India and Australia again met for consultations in Bangkok on the margins of the East Asia Summit. Statements were issued separately by the four countries. Indian Ministry of External Affairs said “In statements issued separately by the four countries, MEA said, “proceeding from the strategic guidance of their Ministers, who met in New York City on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly recently, the officials exchanged views on ongoing and additional practical cooperation in the areas of connectivity and infrastructure development, and security matters, including counterterrorism, cyber and maritime security, with a view to promoting peace, security, stability, prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.” US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue was held on 18 December, 2019, in Washington DC. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will host Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Shri Rajnath Singh. The discussion focussed on deepening bilateral strategic and defense cooperation, exchanging perspectives on global developments, and our shared leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.The two democracies signed the Industrial Security Annex before the 2+2 Dialogue. Assessments of the situation in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean region in general were shared between both countries. (

US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue was held on 18 December, 2019, in Washington DC. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will host Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Shri Rajnath Singh. The discussion focussed on deepening bilateral strategic and defense cooperation, exchanging perspectives on global developments, and our shared leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.The two democracies signed the Industrial Security Annex before the 2+2 Dialogue. Assessments of the situation in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean region in general were shared between both countries. ( The foreign ministers of QUAD continued their discussions from the last ministerial level meeting in 2019, on 6 October, 2020. While there was no joint statement released, all countries issued individual readouts. As per the issue readout by India, the discussion called for a coordinated response to the challenges including financial problems emanating from the pandemic, best practices to combat Covid-19, increasing the resilience of supply chains, and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicines and medical equipment. There was also a focus on maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region amidst growing tensions. Australian media release mentions “We emphasised that, especially during a pandemic, it was vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity. Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).”

The foreign ministers of QUAD continued their discussions from the last ministerial level meeting in 2019, on 6 October, 2020. While there was no joint statement released, all countries issued individual readouts. As per the issue readout by India, the discussion called for a coordinated response to the challenges including financial problems emanating from the pandemic, best practices to combat Covid-19, increasing the resilience of supply chains, and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicines and medical equipment. There was also a focus on maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region amidst growing tensions. Australian media release mentions “We emphasised that, especially during a pandemic, it was vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity. Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).” On September 24, President Biden hosted Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan at the White House for the first-ever in-person Leaders’ Summit of the QUAD. The leaders released a Joint Statement which summarised their dialogue and future course of action. The regional security of the Indo-Pacific and strong confidence in the ASEAN remained on the focus along with response to the Pandemic.

On September 24, President Biden hosted Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan at the White House for the first-ever in-person Leaders’ Summit of the QUAD. The leaders released a Joint Statement which summarised their dialogue and future course of action. The regional security of the Indo-Pacific and strong confidence in the ASEAN remained on the focus along with response to the Pandemic.  The QUAD Vaccine Partnership was announced at the first QUAD Summit on 12 March 2021 where QUAD countries agreed to deliver 1.2 billion vaccine doses globally. The aim was to expand and finance vaccine manufacturing and equipping the Indo-Pacific to build resilience against Covid-19. The launch of a senior-level QUAD Vaccine Experts Group, comprised of top scientists and officials from all QUAD member governments was also spearheaded.

The QUAD Vaccine Partnership was announced at the first QUAD Summit on 12 March 2021 where QUAD countries agreed to deliver 1.2 billion vaccine doses globally. The aim was to expand and finance vaccine manufacturing and equipping the Indo-Pacific to build resilience against Covid-19. The launch of a senior-level QUAD Vaccine Experts Group, comprised of top scientists and officials from all QUAD member governments was also spearheaded.  Although the Tsunami Core group had to be disbanded on fulfilment of its purpose, however the quadrilateral template that formed remained intact as a successful scaffolding of four countries, as stated by authors Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland in their diplomatic brief about QUAD ( you can access the brief at

Although the Tsunami Core group had to be disbanded on fulfilment of its purpose, however the quadrilateral template that formed remained intact as a successful scaffolding of four countries, as stated by authors Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland in their diplomatic brief about QUAD ( you can access the brief at  Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the Core Tsunami Group was to be disbanded and folded and clubbed with the broader United Nations led Relief Operations. In a Tsunami Relief Conference in Jakarta, Secretary Powell stated that

Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the Core Tsunami Group was to be disbanded and folded and clubbed with the broader United Nations led Relief Operations. In a Tsunami Relief Conference in Jakarta, Secretary Powell stated that  Soon after the Earthquake and Tsunami crisis, humanitarian reliefs by countries, viz., US, India, Japan, and Australia started to help the 13 havoc-stricken countries. The US initially promised $ 35 Millions in aid. However, on 29

Soon after the Earthquake and Tsunami crisis, humanitarian reliefs by countries, viz., US, India, Japan, and Australia started to help the 13 havoc-stricken countries. The US initially promised $ 35 Millions in aid. However, on 29 At 7:59AM local time, an earthquake of 9.1 magnitude (undersea) hit the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island. As a result of the same, massive waves of Tsunami triggered by the earthquake wreaked havoc for 7 hours across the Indian Ocean and to the coastal areas as far away as East Africa. The infamous Tsunami killed around 225,000 people, with people reporting the height of waves to be as high as 9 metres, i.e., 30 feet. Indonesia, Srilanka, India, Maldives, Thailand sustained horrendously massive damage, with the death toll exceeding 200,000 in Northern Sumatra’s Ache province alone. A great many people, i.e., around tens of thousands were found dead or missing in Srilanka and India, mostly from Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Indian territory. Maldives, being a low-lying country, also reported casualties in hundreds and more, with several non-Asian tourists reported dead or missing who were vacationing. Lack of food, water, medicines burgeoned the numbers of casualties, with the relief workers finding it difficult to reach the remotest areas where roads were destroyed or civil war raged. Long-term environmental damage ensued too, as both natural and man-made resources got demolished and diminished.

At 7:59AM local time, an earthquake of 9.1 magnitude (undersea) hit the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island. As a result of the same, massive waves of Tsunami triggered by the earthquake wreaked havoc for 7 hours across the Indian Ocean and to the coastal areas as far away as East Africa. The infamous Tsunami killed around 225,000 people, with people reporting the height of waves to be as high as 9 metres, i.e., 30 feet. Indonesia, Srilanka, India, Maldives, Thailand sustained horrendously massive damage, with the death toll exceeding 200,000 in Northern Sumatra’s Ache province alone. A great many people, i.e., around tens of thousands were found dead or missing in Srilanka and India, mostly from Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Indian territory. Maldives, being a low-lying country, also reported casualties in hundreds and more, with several non-Asian tourists reported dead or missing who were vacationing. Lack of food, water, medicines burgeoned the numbers of casualties, with the relief workers finding it difficult to reach the remotest areas where roads were destroyed or civil war raged. Long-term environmental damage ensued too, as both natural and man-made resources got demolished and diminished.

No responses yet