– By Amisha Das

“Andaman and Nicobar Islands are very strategically located. They overlook the entire sea lines of communication and choke lines (in the Indian Ocean Region).” – Navy Chief Admiral R. K. Dhowan.

The Indian Ocean Region (IOR), which remained quiet for some time after the Cold War has re-emerged as a critical theatre for strategic competition, with China expanding its presence in the IOR, India has formulated a new maritime approach to retain its prominence in the region with the Andaman and Nicobar Islands at the center of its plan.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands (ANI) are two groups of islands expanding over an area of 8,294 sq km. The entire island chain of 836 islands, often referred to as one of the most strategically located island chains in the world, is critical to India’s strategic interests in the IOR and Indo-Pacific. They comprise the sole archipelago in the Bay of Bengal, overlooking important sea lines of communication and choke lines. The significance of the ANI has been well known even during the 11th century Chola dynasty when the king was said to have a strategic naval base to send the expeditions into Indonesia.

The ANI is not only geographically far away from India but for most of the 20th century, has also been far away from the consciousness of Indians, owing to the long-standing ‘protectionist’ approach, to preserve the islands in its “existential setting against the pulls of exploitative enticements.” Recently the rising national interest to strengthen ties with Southeast Asia has led to a change in strategy in the governance of the islands- to ensure “all-round national development”, and largely owed to the greater Chinese presence in the IOR, threatening the freedom of navigation. In the quest for new energy resources in the region, China has acquired a foothold in critical junctures of Chittagong, Hambantota, Gwadar, and Kyankpyu popularly known as the “String of Pearls.”

Strategic Importance vis-à-vis geography of Andaman and Nicobar Islands

To make the ANI more relevant to India’s security and development goals, the answer lies in its geography. The islands are located closer to Southeast Asian countries than to the Indian mainland— the Landfall islands, the northernmost tip of the island groups is only 20 km away from Coco islands, Myanmar; Port Blair, the capital of the union territory is 668 km away from Ranong coast, Thailand and the southernmost tip of the ANI, the Indira Point is 80 km from Sumatra in Indonesia. Other than the geographical proximity, ANI’s physical layout provides for a vital role in ensuring maritime security in the region.

The ANI overlooks the Preparis Channel, the Ten and Six Degree Channels, Duncan’s Passage, and the Malacca Strait- the juncture of Indian and Pacific Oceans. A major sea line of communication, nearly 40% of the world trade (about 250 ships per day) transit through the Six Degree Channel, owing to the ANI’s location, India has a great advantage in monitoring these transits via the Indian Ocean along with projecting military strength into Southeast Asia and beyond. Similarly, the Ten-Degree Channel, through which the majority of trade passes from the South China Sea and the Pacific, into the Indian Ocean, is right between the north and south Nicobar islands. By virtue of the ANI, India controls 2.1 million sq km of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which is nearly 30% of India’s total EEZ.

Over the years ANI has been a ‘staging post’ for humanitarian efforts, traditionally by India in the Bay of Bengal. Especially by the Indian Navy, building on its 2004 tsunami relief experience, the Navy has undertaken a wide range of Human Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) operations in the regional seas, ranging from major evacuation efforts in Yemen to alleviating the drinking water crisis in the Maldives and providing relief supplies to Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Indonesia during these natural disasters.

Countering the China factor

Known as the ‘manufacturing hub’ of the world, the majority of China’s exports are transported via the Malacca Strait. And almost 80% of China’s energy requirements, i.e oil and gas are transferred through the Channel and Malacca Strait. To overcome what is called China’s ‘Malacca Dilemma’, the Chinese have set out to expand their footprint in the IOR and fulfill their maritime Silk Road ambitions that have “fueled apprehensions about freedom of navigation in these waters.” January 2020, six Chinese research vessels were spotted in the IOR, and a survey ship, Xiang Yang Hong 03, was accused of running dark or operating without transmitting its position in the Indonesian waters, heading towards the Indian Ocean in January 2021.

Considering this growing Chinese presence, two consequences can be expected in the IOR— firstly, by gaining ground of these crucial chokepoints, China could use them to their advantage during a standoff with India or any other adversary, since all major countries like Japan, Australia, etc rely on these passages for their oil and gas imports; and secondly, a counterbalance by the Indian Navy can be expected, including an increased deployment of anti-submarine warfare aircraft in the ANI.

To counter China, India is working with partner countries on developmental and military projects. A crucial collaboration, the United States and Japan- ‘Sound Surveillance System’ (SOSUS)- a chain of sensors designed to track submarines has been set up creating a counter wall of sorts against the Chinese submarines loitering in the Andaman Sea and the deep South China Sea, this intelligence will be shared by Japan with the United Kingdom, Australia, and India. In 2018, India and Indonesia reached an agreement to establish a special task force to develop connectivity between the post of Sabang and ANI, under their “Shared Vision of India-Indonesia Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.”

In addition, the development of a transshipment port at Great Nicobar, which is located close to the Malacca Strait and the East-West shipping route connecting Europe and Africa with Asia, is underway. Other developmental projects include the optic fiber connectivity between Chennai and Port Blair facilitating telecom connectivity, two bridges on the Andaman Trunk Road, an extension of Diglipur airport runway, and the ‘Pawan Hans’ helicopter service for better inter-island connectivity, to name a few.

Often referred to as the ‘unsinkable aircraft carriers’, India’s first tri-service command- Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC) was established in 2001. India’s military presence in the IOR got a boost with the commission of a full-fledged naval base, INS Kohassa in North Andaman Island. A ten-year “roll-on” plan at an estimated cost of five thousand crore rupees is being worked out for creating new, improving and strengthening existing military infrastructure for additional troops, warships, aircraft, and drones in the ANC. Leveraging the locational proximity to Southeast Asia, the ANC conducts joint maritime exercises such as the Singapore India Maritime Bilateral Exercise and Coordinated Patrols with Myanmar, Thailand, and Indonesia. It also conducts MILAN, a biennial multilateral naval exercise, to build friendship across the seas. Twenty countries participated in the 2018 edition, making it the largest naval exercise in the Andaman Sea.

Conclusion

The IOR is termed as a global highway through which the majority of the oil and cargo passes to and fro the Indian Ocean and Pacific. It is also seen as a theatre of strategic contestation; if one looks at the geopolitical games that are being played in the Indo-Pacific region, most of them are played in the IOR. Unlike the South China Sea which can be said to be a contested theatre with live disputes leading to a virtual gridlock reducing the capacity of power projection; the IOR is an open ocean with room for power projection by China, the US, Australia, Japan, France, and India- who considers the IOR to be a veritable backyard. Hence for India, protecting its takes in the IOR where it faces several traditional and non-traditional threats is critical. This is where the ANI becomes important- as a strategic outpost to defend vital stakes in the IOR and beyond.

The building of defense infrastructure and commissioning new naval bases, along with collaborations with like-minded democracies are steps in the right direction as these underscore India’s stakes in this emerging and important theatre. Though these developments should go hand in hand with cooperation and confidence by countries in the IOR, since in the mid-1990s when India began developing a military presence in the ANI, Malaysia, and Indonesia, which were interested in terms of development and harnessing the strategic capabilities of the ANI initially did not see the projections of ANI as positive developments.

From the logic of ‘minimalist security’ presence sought by many nations in terms of preserving peace and prosperity in the IOR to active military developments, it will be essential to note how the geopolitical and maritime security dynamics evolve with the months and years to come, with contestations for control and recognition of ANI to counter the Chinese aggression by India and stakeholder nations, as well as to springboard trade and commerce, as per India’s ‘Act East Policy.’

References :

- https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ORF_IssueBrief_495_AndamanNicobar-1.pdf

- https://www.cescube.com/vp-increasing-strategic-importance-of-andaman-and-nicobar-islands

- https://eurasiantimes.com/lessons-from-ladakh-india-to-enhance-defence-capabilities-in-andaman-nicobar-islands-to-keep-china-away/

- https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/the-andaman-and-nicobar-islands-new-delhis-bulwark-in-the-indian-ocean/

onducted a total of five underground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Pakistan followed, claiming 5 tests on May 28, 1998, and an additional test on May 30. The unannounced tests created a global storm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in South Asia. On May 13, 1998, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctions on India, mandated by Section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and applied the same sanctions to Pakistan on May 30. Some effects of the sanctions on India included: termination of $21 million in FY1998 economic development assistance; postponement of $1.7 billion in lending by the International Financial Institutions (IFI), as supported by the Group of Eight (G-8) leading industrial nations; prohibition on loans or credit from U.S. banks to the government of India; and termination of Foreign Military Sales under the Arms Export Control Act. Humanitarian assistance, food, or other agricultural commodities are excepted from sanctions under the law.

onducted a total of five underground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Pakistan followed, claiming 5 tests on May 28, 1998, and an additional test on May 30. The unannounced tests created a global storm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in South Asia. On May 13, 1998, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctions on India, mandated by Section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and applied the same sanctions to Pakistan on May 30. Some effects of the sanctions on India included: termination of $21 million in FY1998 economic development assistance; postponement of $1.7 billion in lending by the International Financial Institutions (IFI), as supported by the Group of Eight (G-8) leading industrial nations; prohibition on loans or credit from U.S. banks to the government of India; and termination of Foreign Military Sales under the Arms Export Control Act. Humanitarian assistance, food, or other agricultural commodities are excepted from sanctions under the law.

The first ministerial level meeting of QUAD was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Before this, the QUAD had

The first ministerial level meeting of QUAD was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Before this, the QUAD had AusIndEx is an exercise between India and Australia which was first held in 2015.The Australian

AusIndEx is an exercise between India and Australia which was first held in 2015.The Australian

On recommendations of the Japanese government, the four countries met at Manila, Philippines for ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) originally, but also ended up having a meeting of what we call the first meeting of four nation states on issues of

On recommendations of the Japanese government, the four countries met at Manila, Philippines for ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) originally, but also ended up having a meeting of what we call the first meeting of four nation states on issues of  On his official visit to India, Japanese PM Mr. Shinzo Abe reinforced the ties of two nations, i.e., Japan and India with his famous speech about

On his official visit to India, Japanese PM Mr. Shinzo Abe reinforced the ties of two nations, i.e., Japan and India with his famous speech about  In 2007, Japanese President Shinzo Abe resigned from his post citing health reasons. This had a significant impact on QUAD as he was the architect & advocate of QUAD. His successor, Yasuo Fukuda, did not take up QUAD with such zeal leading to dormancy of the forum. (

In 2007, Japanese President Shinzo Abe resigned from his post citing health reasons. This had a significant impact on QUAD as he was the architect & advocate of QUAD. His successor, Yasuo Fukuda, did not take up QUAD with such zeal leading to dormancy of the forum. ( Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, also called Great Sendai Earthquake or Great Tōhoku Earthquake, was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake which struck below the floor of the Western Pacific at 2:49 PM. The powerful earthquake affected the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island, and also initiated a series of large tsunami waves that devastated coastal areas of Japan, which also led to a major nuclear accident. Japan received aid from India, US, Australia as well as other countries. US Navy aircraft carrier was dispatched to the area and Australia sent search-and-rescue teams.

Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, also called Great Sendai Earthquake or Great Tōhoku Earthquake, was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake which struck below the floor of the Western Pacific at 2:49 PM. The powerful earthquake affected the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island, and also initiated a series of large tsunami waves that devastated coastal areas of Japan, which also led to a major nuclear accident. Japan received aid from India, US, Australia as well as other countries. US Navy aircraft carrier was dispatched to the area and Australia sent search-and-rescue teams.  India and Australia signed the

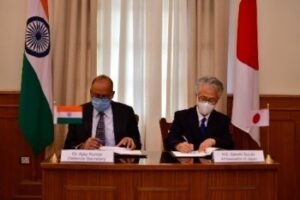

India and Australia signed the  The India-Japan Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy was signed on 11 November, 2016 and came into force on 20 July, 2017 which was representative of strengthening ties between India and Japan. Diplomatic notes were exchanged between Dr. S. Jaishankar and H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India. (

The India-Japan Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy was signed on 11 November, 2016 and came into force on 20 July, 2017 which was representative of strengthening ties between India and Japan. Diplomatic notes were exchanged between Dr. S. Jaishankar and H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India. ( The foreign ministry

The foreign ministry The Officials of QUAD member countries met in Singapore on November 15, 2018 for consultation on regional & global issues of common interest. The main discussion revolved around connectivity, sustainable development, counter-terrorism, maritime and cyber security, with the view to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the

The Officials of QUAD member countries met in Singapore on November 15, 2018 for consultation on regional & global issues of common interest. The main discussion revolved around connectivity, sustainable development, counter-terrorism, maritime and cyber security, with the view to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the  The 23rd edition of trilateral Malabar maritime exercise between India, US and Japan took place on 26 September- 04 October, 2019 off the coast of Japan.

The 23rd edition of trilateral Malabar maritime exercise between India, US and Japan took place on 26 September- 04 October, 2019 off the coast of Japan.  After the first ministerial level meeting of QUAD in September, 2019, the senior officials of US, Japan, India and Australia again met for consultations in Bangkok on the margins of the East Asia Summit. Statements were issued separately by the four countries. Indian Ministry of External Affairs said “In statements issued separately by the four countries, MEA said, “proceeding from the strategic guidance of their Ministers, who met in New York City on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly recently, the officials exchanged views on ongoing and additional practical cooperation in the areas of connectivity and infrastructure development, and security matters, including counterterrorism, cyber and maritime security, with a view to promoting peace, security, stability, prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.”

After the first ministerial level meeting of QUAD in September, 2019, the senior officials of US, Japan, India and Australia again met for consultations in Bangkok on the margins of the East Asia Summit. Statements were issued separately by the four countries. Indian Ministry of External Affairs said “In statements issued separately by the four countries, MEA said, “proceeding from the strategic guidance of their Ministers, who met in New York City on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly recently, the officials exchanged views on ongoing and additional practical cooperation in the areas of connectivity and infrastructure development, and security matters, including counterterrorism, cyber and maritime security, with a view to promoting peace, security, stability, prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.” US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue was held on 18 December, 2019, in Washington DC. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will host Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Shri Rajnath Singh. The discussion focussed on deepening bilateral strategic and defense cooperation, exchanging perspectives on global developments, and our shared leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.The two democracies signed the Industrial Security Annex before the 2+2 Dialogue. Assessments of the situation in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean region in general were shared between both countries. (

US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue was held on 18 December, 2019, in Washington DC. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will host Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Shri Rajnath Singh. The discussion focussed on deepening bilateral strategic and defense cooperation, exchanging perspectives on global developments, and our shared leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.The two democracies signed the Industrial Security Annex before the 2+2 Dialogue. Assessments of the situation in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean region in general were shared between both countries. ( The foreign ministers of QUAD continued their discussions from the last ministerial level meeting in 2019, on 6 October, 2020. While there was no joint statement released, all countries issued individual readouts. As per the issue readout by India, the discussion called for a coordinated response to the challenges including financial problems emanating from the pandemic, best practices to combat Covid-19, increasing the resilience of supply chains, and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicines and medical equipment. There was also a focus on maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region amidst growing tensions. Australian media release mentions “We emphasised that, especially during a pandemic, it was vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity. Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).”

The foreign ministers of QUAD continued their discussions from the last ministerial level meeting in 2019, on 6 October, 2020. While there was no joint statement released, all countries issued individual readouts. As per the issue readout by India, the discussion called for a coordinated response to the challenges including financial problems emanating from the pandemic, best practices to combat Covid-19, increasing the resilience of supply chains, and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicines and medical equipment. There was also a focus on maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region amidst growing tensions. Australian media release mentions “We emphasised that, especially during a pandemic, it was vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity. Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).” On September 24, President Biden hosted Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan at the White House for the first-ever in-person Leaders’ Summit of the QUAD. The leaders released a Joint Statement which summarised their dialogue and future course of action. The regional security of the Indo-Pacific and strong confidence in the ASEAN remained on the focus along with response to the Pandemic.

On September 24, President Biden hosted Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan at the White House for the first-ever in-person Leaders’ Summit of the QUAD. The leaders released a Joint Statement which summarised their dialogue and future course of action. The regional security of the Indo-Pacific and strong confidence in the ASEAN remained on the focus along with response to the Pandemic.  The QUAD Vaccine Partnership was announced at the first QUAD Summit on 12 March 2021 where QUAD countries agreed to deliver 1.2 billion vaccine doses globally. The aim was to expand and finance vaccine manufacturing and equipping the Indo-Pacific to build resilience against Covid-19. The launch of a senior-level QUAD Vaccine Experts Group, comprised of top scientists and officials from all QUAD member governments was also spearheaded.

The QUAD Vaccine Partnership was announced at the first QUAD Summit on 12 March 2021 where QUAD countries agreed to deliver 1.2 billion vaccine doses globally. The aim was to expand and finance vaccine manufacturing and equipping the Indo-Pacific to build resilience against Covid-19. The launch of a senior-level QUAD Vaccine Experts Group, comprised of top scientists and officials from all QUAD member governments was also spearheaded.  Although the Tsunami Core group had to be disbanded on fulfilment of its purpose, however the quadrilateral template that formed remained intact as a successful scaffolding of four countries, as stated by authors Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland in their diplomatic brief about QUAD ( you can access the brief at

Although the Tsunami Core group had to be disbanded on fulfilment of its purpose, however the quadrilateral template that formed remained intact as a successful scaffolding of four countries, as stated by authors Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland in their diplomatic brief about QUAD ( you can access the brief at  Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the Core Tsunami Group was to be disbanded and folded and clubbed with the broader United Nations led Relief Operations. In a Tsunami Relief Conference in Jakarta, Secretary Powell stated that

Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the Core Tsunami Group was to be disbanded and folded and clubbed with the broader United Nations led Relief Operations. In a Tsunami Relief Conference in Jakarta, Secretary Powell stated that  Soon after the Earthquake and Tsunami crisis, humanitarian reliefs by countries, viz., US, India, Japan, and Australia started to help the 13 havoc-stricken countries. The US initially promised $ 35 Millions in aid. However, on 29

Soon after the Earthquake and Tsunami crisis, humanitarian reliefs by countries, viz., US, India, Japan, and Australia started to help the 13 havoc-stricken countries. The US initially promised $ 35 Millions in aid. However, on 29 At 7:59AM local time, an earthquake of 9.1 magnitude (undersea) hit the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island. As a result of the same, massive waves of Tsunami triggered by the earthquake wreaked havoc for 7 hours across the Indian Ocean and to the coastal areas as far away as East Africa. The infamous Tsunami killed around 225,000 people, with people reporting the height of waves to be as high as 9 metres, i.e., 30 feet. Indonesia, Srilanka, India, Maldives, Thailand sustained horrendously massive damage, with the death toll exceeding 200,000 in Northern Sumatra’s Ache province alone. A great many people, i.e., around tens of thousands were found dead or missing in Srilanka and India, mostly from Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Indian territory. Maldives, being a low-lying country, also reported casualties in hundreds and more, with several non-Asian tourists reported dead or missing who were vacationing. Lack of food, water, medicines burgeoned the numbers of casualties, with the relief workers finding it difficult to reach the remotest areas where roads were destroyed or civil war raged. Long-term environmental damage ensued too, as both natural and man-made resources got demolished and diminished.

At 7:59AM local time, an earthquake of 9.1 magnitude (undersea) hit the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island. As a result of the same, massive waves of Tsunami triggered by the earthquake wreaked havoc for 7 hours across the Indian Ocean and to the coastal areas as far away as East Africa. The infamous Tsunami killed around 225,000 people, with people reporting the height of waves to be as high as 9 metres, i.e., 30 feet. Indonesia, Srilanka, India, Maldives, Thailand sustained horrendously massive damage, with the death toll exceeding 200,000 in Northern Sumatra’s Ache province alone. A great many people, i.e., around tens of thousands were found dead or missing in Srilanka and India, mostly from Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Indian territory. Maldives, being a low-lying country, also reported casualties in hundreds and more, with several non-Asian tourists reported dead or missing who were vacationing. Lack of food, water, medicines burgeoned the numbers of casualties, with the relief workers finding it difficult to reach the remotest areas where roads were destroyed or civil war raged. Long-term environmental damage ensued too, as both natural and man-made resources got demolished and diminished.

No responses yet