– By Pragyadeepta Dasgupta

Introduction

As I had reckoned once from a 2019 case, a 19-year-old had first gained universal attention when she was seen pleading, through television and newspaper interviews, to return to the UK, who, then a mere 15-year-old, had left East London for Syria to travel with the ISIS. It raises multiple doubts surrounding the connection between trafficking and terrorism, whether these terrorist organization child recruits were victims of trafficking themselves. Human and sex trafficking continue to evolve with the perpetrators switching and applying more cultivated and inter-professional methods of carrying out their actions. These methods are often subtle and hence mostly go under the radar and have become very difficult to be dealt with and combated by the security forces of almost every country. Multiple reports hint a sequence of connection between trafficking and terrorism. A very recent report produced by OHCHR states that “victims of trafficking by terrorist groups are too often being punished, instead of protected.”1 The report mentions how states have constantly failed to identify these victims and protect them because of suspicions lying around their apparent collaboration with terrorist groups, and related blot on one’s escutcheon, discrimination and racism. Human rights activists have constantly expressed their disappointment regarding the same.

Various U.N. Security Council actions have considered how terrorists benefit from transnational organized crime (e.g., resolutions 2195 (2014), 2253 (2015), 2322 (2016), 2347 (2017) and 2368 (2017)). On at least three occasions, the Council has specifically examined the relationship of trafficking and sexual violence in armed conflict with terrorism and other transnational criminal activities (2015), resolutions 2331 (2016) and 2388 (2017)). And in resolution 2242 in 2015, the Council explored how acts of sexual and gender-based violence are part of the strategic objectives and ideology of certain terrorist groups.2

On a collective note, these resolutions are to highlight the fact that terrorist organizations have always used human trafficking as a hack for more enrollment (e.g., using female trafficking victims to attract and retain fighters); to increase financial flows; and to strengthen influence, including by controlling or destroying communities involved in or affected by the trafficking.

Sustenance of slavery and trafficking

Although the concept of sexual terrorism has been used in the past, it has recently received increased attention due to the activities of terrorist organizations such as not only ISIS, but also Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram. When these terrorist groups use CRSV (Conflict Related Sexual Violence) and human trafficking as a tactic of terrorism, one could speak of sexual terrorism. The nexus between these forms of criminality has been gradually recognized, including at the international level. For example, in UN Security Council Resolution 2331 of 20 December 2016, the Council expressed its deep concern that:

acts of sexual and gender-based violence, including when associated to human trafficking, are known to be part of the strategic objectives and ideology of certain terrorist groups, used as a tactic of terrorism and an instrument to increase their finances and their power through recruitment and the destruction of communities.3

Sexual violence and human trafficking by ISIS have demonstrated itself in different ways, the most visible aspect being (especially female) sexual enslavement. Every year thousands of women and girls, particularly Christians and Yezidis, have been abducted by ISIS, after which the women were either stationed in brothels or sold as sex slaves on the market. Such practices, – instructed by ISIS (it published guidelines in December 2014 on how to capture, forcibly hold, and sexually abuse female slaves, and even had a Department of Slaves)4 The topic of sexual terrorism has been prevalent and to address sexual violence committed by these organizations it was justified by ISIS “as permissible conduct towards non-believers who refuse to accede to Islam.” Hence, and as also explained in an earlier ICCT perspective by Nadia Al-Dayel and Andrew Mumford, sexual terrorism by ISIS was extremely widespread, organized and institutionalized. It has been used, among other things, to further its ideology, to crush and terrorize opposing communities, to recruit new fighters (and to keep those recruited inside the organization), and to increase the organization’s financial resources.5

Most victims have been trafficked for sexual exploitation and for forced labor which are the most prominently detected forms, but these victims can also be exploited in other ways. Victims are trafficked to be used as beggars, for forced or sham marriages, benefit fraud, production of pornography or for organ removal. The clear majority of the detected victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation (the most commonly detected form of trafficking) are females, while more than half of the victims of trafficking for forced labor are men (UNODC (b), 2018).6

It has been 8 years since the Sinjar massacre happened which was instigated by the terrorist organization ‘Islamic States’ (Daesh). As each year passes, the issue may feel further removed for people not directly affected. Yet—for those awaiting family members to return—it marks yet another year in which the perpetrators of this crime against humanity are not brought to justice. The numbers of the Sinjar attack are shocking. More than 6,000 Yazidis—mostly children and women—were kidnapped in early August 2014. Hundreds of men were executed upon capture. Half of those kidnapped are reportedly still missing, suspected of being further entrenched in human trafficking operations or killed.7 Cases of kidnapping, slavery and sexual violence are quite uncommon for conflicts but the scale and structural elements of the Islamic States slavery economy is new. The cases of slavery and sexual violence is spreading at great lengths and depths across the occupied territories of Syria and Iraq and is growing at concerning rate. The depths at which these crimes are permeated into the socio-economic culture of the organization and even the families in the Islamic States- including foreign fighters. According to Iraqi MP Vian Dakhil, herself a Yazidi from Sinjar, an estimated 6,383 Yazidis – mostly women and children – were enslaved and transported to ISIS prisons, military training camps, and the homes of fighters across eastern Syria and western Iraq, where they were raped, beaten, sold, and locked away.8

Many of the stories about the abduction and enslavement of Yazidi women and children described them as “sex slaves” and featured graphic, sometimes lurid, accounts by newly escaped survivors. The female fighters of Kurdish militias helping to free Yazidis from Mount Sinjar became fodder for often novelty coverage. The Yazidis became the embodiment of embattled, exotic minorities set against the evil of ISIS. This narrative has stereotyped Yazidi women as passive victims of mass rape at the hands of perpetrators presented as the epitome of pure evil.9

ISIS describes its own use of enslavement through a mix of clumsy metaphors about sex, war and power. Dividing up the captive women and children among the ISIS mujahideen (holy warriors) and “sanctioning their genitals” is described as a sign of “realization and dominance by the sword”.10 Katherine E Brown, a lecturer in Islamic studies at the University of Birmingham, explained that ISIS mainly justifies its use of slavery through selective interpretations of the hadith, the reported accounts of the life and sayings of Muhammad and his companions: “They justify it on the basis that it is a reward for carrying out services for the community – slaves are presented as compensation for fighters. However, they chose particular ways of seeing these hadith, and selectively choose them so as to ignore, for example, the requirement not to kill your prisoners by focusing on the requirement to make sure they ‘don’t escape’ by being ‘secured at the neck’ until negotiations have taken place.”11

Policies that could help curb the issue

A broad range of steps related to advancing a normative framework, enhancing international co-operation and developing regional assistance are recommended to improve the international response to the intersection of terrorism and trafficking in human beings. Prevention ideas should be tailored according to border and cross border strategies to prevent and combat human trafficking. Strategies should include measures that consider and are geared at aspects of gender and age in human trafficking, raising awareness about the risks of human trafficking and terrorism; reducing vulnerability of at-risk populations, protection and assistance to victims of both crimes to ensure their rehabilitation and re-integration and prevent their re-victimization. Assessing the risk of human trafficking being involved in suspicious transactions that suggest money laundering and terrorism financing can help disrupt the business models of both crimes and lead to both victims and perpetrators being identified. applying the protective measures that exist in anti-trafficking frameworks for victims of trafficking committed by terrorist groups; and aligning legal doctrines when addressing individual crimes to allow for the consistent and fair application of law in situations where crimes overlap.12

Conclusion

As the establishment of numerous ISIS wilayats around the world proliferates and the re-emergence of ISIS in parts of northern Syria—facilitated by the recent prison breaks in the wake of American withdrawal from Kurdish areas—continues apace, the capacity for more communities to be forcibly pressed into slavery looms dangerously large. Where ISIS goes, slavery follows—engendering overlapping conditions of sexual and political violence, demonstrating that the slaves of ISIS are also victims of terrorism.13 Unfortunately the international response has been ponderous and dogmatic. An indefinite “wait-and-see” approach by western governments, megaphone diplomacy, illicit flows will all exacerbate a growing humanitarian, financial, and security crisis with regional and global ramifications. Humanitarian and development funding have to be delivered now, and at scale.14

References :

1 OHCHR- Human trafficking victims must be protected even in fight against terrorism

2 James Huckerby (2009). When Human Trafficking and Terrorism Connect: Dangers and Dilemmas.

3-5 Dr. Christophe Paulussen (2021). ISIS and Sexual Terrorism: Scope, Challenges and the (Mis)Use of the Label.

6 UNODC- Trafficking in persons and terrorism

7 Nadia Al-Dayel, Andrew Mumford (2020). ISIS and Their Use of Slavery

8-11 Cathy Otten (2017). Slaves of ISIS: Long walk of the Yazidi women

12 OSR/CTHB, (2019) Following the Money: Compendium of Resources and Step-by-Step Guide to Financial Investigations related to Trafficking in Human Beings.

13 Nadia Al-Dayel, Andrew Mumford (2020). ISIS and Their Use of Slavery

14 Jonathan Goodhand, Jan Koehler (2021). Heroin and human trafficking are the only two sectors of Afghanistan economy still thriving.

onducted a total of five underground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Pakistan followed, claiming 5 tests on May 28, 1998, and an additional test on May 30. The unannounced tests created a global storm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in South Asia. On May 13, 1998, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctions on India, mandated by Section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and applied the same sanctions to Pakistan on May 30. Some effects of the sanctions on India included: termination of $21 million in FY1998 economic development assistance; postponement of $1.7 billion in lending by the International Financial Institutions (IFI), as supported by the Group of Eight (G-8) leading industrial nations; prohibition on loans or credit from U.S. banks to the government of India; and termination of Foreign Military Sales under the Arms Export Control Act. Humanitarian assistance, food, or other agricultural commodities are excepted from sanctions under the law.

onducted a total of five underground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Pakistan followed, claiming 5 tests on May 28, 1998, and an additional test on May 30. The unannounced tests created a global storm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in South Asia. On May 13, 1998, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctions on India, mandated by Section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), and applied the same sanctions to Pakistan on May 30. Some effects of the sanctions on India included: termination of $21 million in FY1998 economic development assistance; postponement of $1.7 billion in lending by the International Financial Institutions (IFI), as supported by the Group of Eight (G-8) leading industrial nations; prohibition on loans or credit from U.S. banks to the government of India; and termination of Foreign Military Sales under the Arms Export Control Act. Humanitarian assistance, food, or other agricultural commodities are excepted from sanctions under the law.

The first ministerial level meeting of QUAD was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Before this, the QUAD had

The first ministerial level meeting of QUAD was held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Before this, the QUAD had AusIndEx is an exercise between India and Australia which was first held in 2015.The Australian

AusIndEx is an exercise between India and Australia which was first held in 2015.The Australian

On recommendations of the Japanese government, the four countries met at Manila, Philippines for ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) originally, but also ended up having a meeting of what we call the first meeting of four nation states on issues of

On recommendations of the Japanese government, the four countries met at Manila, Philippines for ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) originally, but also ended up having a meeting of what we call the first meeting of four nation states on issues of  On his official visit to India, Japanese PM Mr. Shinzo Abe reinforced the ties of two nations, i.e., Japan and India with his famous speech about

On his official visit to India, Japanese PM Mr. Shinzo Abe reinforced the ties of two nations, i.e., Japan and India with his famous speech about  In 2007, Japanese President Shinzo Abe resigned from his post citing health reasons. This had a significant impact on QUAD as he was the architect & advocate of QUAD. His successor, Yasuo Fukuda, did not take up QUAD with such zeal leading to dormancy of the forum. (

In 2007, Japanese President Shinzo Abe resigned from his post citing health reasons. This had a significant impact on QUAD as he was the architect & advocate of QUAD. His successor, Yasuo Fukuda, did not take up QUAD with such zeal leading to dormancy of the forum. ( Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, also called Great Sendai Earthquake or Great Tōhoku Earthquake, was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake which struck below the floor of the Western Pacific at 2:49 PM. The powerful earthquake affected the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island, and also initiated a series of large tsunami waves that devastated coastal areas of Japan, which also led to a major nuclear accident. Japan received aid from India, US, Australia as well as other countries. US Navy aircraft carrier was dispatched to the area and Australia sent search-and-rescue teams.

Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011, also called Great Sendai Earthquake or Great Tōhoku Earthquake, was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake which struck below the floor of the Western Pacific at 2:49 PM. The powerful earthquake affected the northeastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island, and also initiated a series of large tsunami waves that devastated coastal areas of Japan, which also led to a major nuclear accident. Japan received aid from India, US, Australia as well as other countries. US Navy aircraft carrier was dispatched to the area and Australia sent search-and-rescue teams.  India and Australia signed the

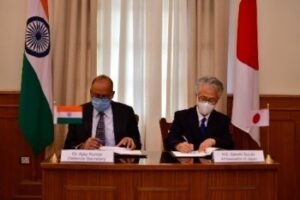

India and Australia signed the  The India-Japan Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy was signed on 11 November, 2016 and came into force on 20 July, 2017 which was representative of strengthening ties between India and Japan. Diplomatic notes were exchanged between Dr. S. Jaishankar and H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India. (

The India-Japan Agreement for Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy was signed on 11 November, 2016 and came into force on 20 July, 2017 which was representative of strengthening ties between India and Japan. Diplomatic notes were exchanged between Dr. S. Jaishankar and H.E. Mr. Kenji Hiramatsu, Ambassador of Japan to India. ( The foreign ministry

The foreign ministry The Officials of QUAD member countries met in Singapore on November 15, 2018 for consultation on regional & global issues of common interest. The main discussion revolved around connectivity, sustainable development, counter-terrorism, maritime and cyber security, with the view to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the

The Officials of QUAD member countries met in Singapore on November 15, 2018 for consultation on regional & global issues of common interest. The main discussion revolved around connectivity, sustainable development, counter-terrorism, maritime and cyber security, with the view to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the  The 23rd edition of trilateral Malabar maritime exercise between India, US and Japan took place on 26 September- 04 October, 2019 off the coast of Japan.

The 23rd edition of trilateral Malabar maritime exercise between India, US and Japan took place on 26 September- 04 October, 2019 off the coast of Japan.  After the first ministerial level meeting of QUAD in September, 2019, the senior officials of US, Japan, India and Australia again met for consultations in Bangkok on the margins of the East Asia Summit. Statements were issued separately by the four countries. Indian Ministry of External Affairs said “In statements issued separately by the four countries, MEA said, “proceeding from the strategic guidance of their Ministers, who met in New York City on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly recently, the officials exchanged views on ongoing and additional practical cooperation in the areas of connectivity and infrastructure development, and security matters, including counterterrorism, cyber and maritime security, with a view to promoting peace, security, stability, prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.”

After the first ministerial level meeting of QUAD in September, 2019, the senior officials of US, Japan, India and Australia again met for consultations in Bangkok on the margins of the East Asia Summit. Statements were issued separately by the four countries. Indian Ministry of External Affairs said “In statements issued separately by the four countries, MEA said, “proceeding from the strategic guidance of their Ministers, who met in New York City on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly recently, the officials exchanged views on ongoing and additional practical cooperation in the areas of connectivity and infrastructure development, and security matters, including counterterrorism, cyber and maritime security, with a view to promoting peace, security, stability, prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.” US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue was held on 18 December, 2019, in Washington DC. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will host Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Shri Rajnath Singh. The discussion focussed on deepening bilateral strategic and defense cooperation, exchanging perspectives on global developments, and our shared leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.The two democracies signed the Industrial Security Annex before the 2+2 Dialogue. Assessments of the situation in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean region in general were shared between both countries. (

US 2+2 Ministerial Dialogue was held on 18 December, 2019, in Washington DC. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper will host Indian Minister of External Affairs Dr. S. Jaishankar and Minister of Defense Shri Rajnath Singh. The discussion focussed on deepening bilateral strategic and defense cooperation, exchanging perspectives on global developments, and our shared leadership in the Indo-Pacific region.The two democracies signed the Industrial Security Annex before the 2+2 Dialogue. Assessments of the situation in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean region in general were shared between both countries. ( The foreign ministers of QUAD continued their discussions from the last ministerial level meeting in 2019, on 6 October, 2020. While there was no joint statement released, all countries issued individual readouts. As per the issue readout by India, the discussion called for a coordinated response to the challenges including financial problems emanating from the pandemic, best practices to combat Covid-19, increasing the resilience of supply chains, and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicines and medical equipment. There was also a focus on maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region amidst growing tensions. Australian media release mentions “We emphasised that, especially during a pandemic, it was vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity. Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).”

The foreign ministers of QUAD continued their discussions from the last ministerial level meeting in 2019, on 6 October, 2020. While there was no joint statement released, all countries issued individual readouts. As per the issue readout by India, the discussion called for a coordinated response to the challenges including financial problems emanating from the pandemic, best practices to combat Covid-19, increasing the resilience of supply chains, and enhancing access to affordable vaccines, medicines and medical equipment. There was also a focus on maintaining stability in the Indo-Pacific region amidst growing tensions. Australian media release mentions “We emphasised that, especially during a pandemic, it was vital that states work to ease tensions and avoid exacerbating long-standing disputes, work to counter disinformation, and refrain from malicious cyberspace activity. Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).” On September 24, President Biden hosted Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan at the White House for the first-ever in-person Leaders’ Summit of the QUAD. The leaders released a Joint Statement which summarised their dialogue and future course of action. The regional security of the Indo-Pacific and strong confidence in the ASEAN remained on the focus along with response to the Pandemic.

On September 24, President Biden hosted Prime Minister Scott Morrison of Australia, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, and Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan at the White House for the first-ever in-person Leaders’ Summit of the QUAD. The leaders released a Joint Statement which summarised their dialogue and future course of action. The regional security of the Indo-Pacific and strong confidence in the ASEAN remained on the focus along with response to the Pandemic.  The QUAD Vaccine Partnership was announced at the first QUAD Summit on 12 March 2021 where QUAD countries agreed to deliver 1.2 billion vaccine doses globally. The aim was to expand and finance vaccine manufacturing and equipping the Indo-Pacific to build resilience against Covid-19. The launch of a senior-level QUAD Vaccine Experts Group, comprised of top scientists and officials from all QUAD member governments was also spearheaded.

The QUAD Vaccine Partnership was announced at the first QUAD Summit on 12 March 2021 where QUAD countries agreed to deliver 1.2 billion vaccine doses globally. The aim was to expand and finance vaccine manufacturing and equipping the Indo-Pacific to build resilience against Covid-19. The launch of a senior-level QUAD Vaccine Experts Group, comprised of top scientists and officials from all QUAD member governments was also spearheaded.  Although the Tsunami Core group had to be disbanded on fulfilment of its purpose, however the quadrilateral template that formed remained intact as a successful scaffolding of four countries, as stated by authors Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland in their diplomatic brief about QUAD ( you can access the brief at

Although the Tsunami Core group had to be disbanded on fulfilment of its purpose, however the quadrilateral template that formed remained intact as a successful scaffolding of four countries, as stated by authors Patrick Gerard Buchan and Benjamin Rimland in their diplomatic brief about QUAD ( you can access the brief at  Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the Core Tsunami Group was to be disbanded and folded and clubbed with the broader United Nations led Relief Operations. In a Tsunami Relief Conference in Jakarta, Secretary Powell stated that

Secretary of State Colin Powell stated that the Core Tsunami Group was to be disbanded and folded and clubbed with the broader United Nations led Relief Operations. In a Tsunami Relief Conference in Jakarta, Secretary Powell stated that  Soon after the Earthquake and Tsunami crisis, humanitarian reliefs by countries, viz., US, India, Japan, and Australia started to help the 13 havoc-stricken countries. The US initially promised $ 35 Millions in aid. However, on 29

Soon after the Earthquake and Tsunami crisis, humanitarian reliefs by countries, viz., US, India, Japan, and Australia started to help the 13 havoc-stricken countries. The US initially promised $ 35 Millions in aid. However, on 29 At 7:59AM local time, an earthquake of 9.1 magnitude (undersea) hit the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island. As a result of the same, massive waves of Tsunami triggered by the earthquake wreaked havoc for 7 hours across the Indian Ocean and to the coastal areas as far away as East Africa. The infamous Tsunami killed around 225,000 people, with people reporting the height of waves to be as high as 9 metres, i.e., 30 feet. Indonesia, Srilanka, India, Maldives, Thailand sustained horrendously massive damage, with the death toll exceeding 200,000 in Northern Sumatra’s Ache province alone. A great many people, i.e., around tens of thousands were found dead or missing in Srilanka and India, mostly from Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Indian territory. Maldives, being a low-lying country, also reported casualties in hundreds and more, with several non-Asian tourists reported dead or missing who were vacationing. Lack of food, water, medicines burgeoned the numbers of casualties, with the relief workers finding it difficult to reach the remotest areas where roads were destroyed or civil war raged. Long-term environmental damage ensued too, as both natural and man-made resources got demolished and diminished.

At 7:59AM local time, an earthquake of 9.1 magnitude (undersea) hit the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island. As a result of the same, massive waves of Tsunami triggered by the earthquake wreaked havoc for 7 hours across the Indian Ocean and to the coastal areas as far away as East Africa. The infamous Tsunami killed around 225,000 people, with people reporting the height of waves to be as high as 9 metres, i.e., 30 feet. Indonesia, Srilanka, India, Maldives, Thailand sustained horrendously massive damage, with the death toll exceeding 200,000 in Northern Sumatra’s Ache province alone. A great many people, i.e., around tens of thousands were found dead or missing in Srilanka and India, mostly from Andaman and Nicobar Islands of Indian territory. Maldives, being a low-lying country, also reported casualties in hundreds and more, with several non-Asian tourists reported dead or missing who were vacationing. Lack of food, water, medicines burgeoned the numbers of casualties, with the relief workers finding it difficult to reach the remotest areas where roads were destroyed or civil war raged. Long-term environmental damage ensued too, as both natural and man-made resources got demolished and diminished.

No responses yet